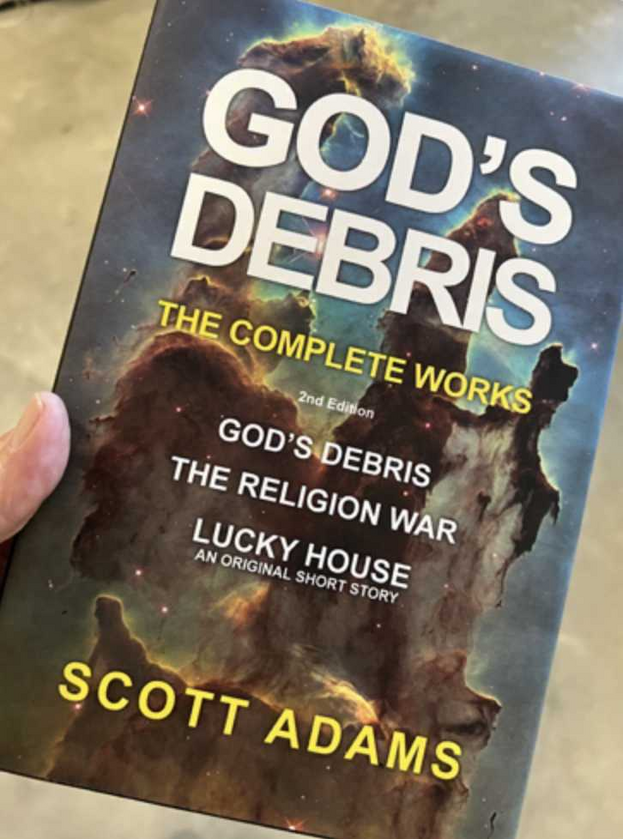

God’s Debris – The Complete Works

The AI Interview

6/7/24

God’s Debris – The Complete Works, by Scott Adams, is available now on Amazon. (Link is in next part of thread.)

Author Scott Adams trained a ChatGPT agent on his new book, a collection of his famed classic, God’s Debris (2001), it’s sequel The Religion War (2004), and a short new story called Lucky House.

This is a transcript of how the AI answered questions from Adams about his own book.

-----

Please describe God's Debris - The Complete Works, in one paragraph or so.

"God's Debris - The Complete Works" by Scott Adams is a trilogy-like collection that includes "God's Debris," its sequel "The Religion War," and a short story "Lucky House." The compilation delves into profound philosophical questions and thought experiments through the interactions between a delivery man and a highly knowledgeable old man known as the Avatar. The works explore themes such as the nature of God, free will, reality, and consciousness, presenting them in a dialogue format that is both accessible and intellectually stimulating. Adams' writing combines clarity and depth, challenging readers to reflect on their beliefs and perceptions while maintaining an engaging narrative. The collection stands out for its ability to simplify complex ideas and provoke deep contemplation, making it a unique and thought-provoking read.

Does Scott Adams use hypnosis techniques in the writing of God’s Debris?

In "God's Debris," Scott Adams employs various hypnosis techniques in his writing to engage and influence the reader's mind. Here are some specific examples:

1. **Suggestion and Visualization**:

- Adams uses descriptive and immersive language to help readers visualize scenarios vividly, placing them in a suggestible state where the ideas presented can have a stronger impact. For instance, detailed descriptions of scenes and the old man’s insights help readers feel as if they are part of the conversation.

2. **Simplification of Complex Ideas**:

- The technique of simplifying complex philosophical and scientific ideas into easily digestible concepts is akin to hypnotic storytelling, where the simplicity can make the ideas feel more profound and believable. Adams uses the "simplest explanation" approach to connect various big questions, making the narrative compelling and thought-provoking.

3. **Pattern Interrupts and Cognitive Dissonance**:

- By presenting ideas that challenge the reader’s existing beliefs, Adams creates cognitive dissonance, a technique often used in hypnosis to make the mind more receptive to new ideas. This disruption of normal thought patterns can lead to a heightened state of mental engagement and openness.

4. **Direct Address and Rhetorical Questions**:

- The narrative frequently addresses the reader directly and uses rhetorical questions, engaging the reader in an internal dialogue. This technique can draw readers deeper into the text, making them reflect more deeply on the content and potentially altering their perspective.

5. **Euphoric Enlightenment**:

- Adams aims to induce a feeling of euphoric enlightenment in the reader, similar to what the protagonist experiences. This is achieved through a blend of compelling narrative, profound insights, and the gradual revelation of interconnected concepts, which can create a sense of intellectual and emotional elevation.

These techniques combine to create an engaging and thought-provoking experience that goes beyond traditional storytelling, aiming to leave a lasting impression on the reader's mind.

Have readers reported a euphoric feeling while reading God’s Debris?

Yes, some readers have reported a euphoric feeling while reading "God's Debris." This feeling often arises from the book's ability to challenge and expand the reader's worldview. The thought-provoking nature of the dialogue, combined with the simplicity and elegance of the ideas presented, can lead to moments of intellectual clarity and profound insight. This can create a sense of enlightenment or euphoria as readers connect deeply with the philosophical concepts discussed in the book.

What can a writer learn about writing by reading the book?

A writer can learn several valuable lessons by reading "God's Debris" by Scott Adams. Here are some key takeaways:

1. **Simplification of Complex Ideas**:

- Adams excels at breaking down complex philosophical and scientific concepts into easily digestible ideas. Writers can learn how to present intricate topics in a way that is accessible and engaging to a broad audience.

2. **Engaging Dialogue**:

- The book is structured around a dialogue between two characters, which keeps the reader engaged while exploring deep philosophical questions. Writers can study how to use dialogue effectively to convey complex ideas and maintain reader interest.

3. **Thought-Provoking Content**:

- "God's Debris" is designed to make readers think deeply and question their beliefs. Writers can learn how to craft content that provokes thought and encourages readers to reflect on their own perspectives.

4. **Clarity and Conciseness**:

- Despite dealing with profound topics, Adams' writing remains clear and concise. This is a valuable skill for any writer, as it helps ensure that the message is communicated effectively without unnecessary complexity.

5. **Innovative Structure**:

- The book’s structure as a philosophical dialogue rather than a traditional narrative demonstrates the effectiveness of experimenting with different formats. Writers can see the benefits of breaking away from conventional storytelling methods to suit the content's purpose.

6. **Engaging Openers**:

- Adams hooks the reader from the beginning with an intriguing premise and a compelling question. Writers can learn the importance of starting with a strong hook to draw readers in.

7. **Balancing Narrative and Philosophy**:

- While "God's Debris" is heavily philosophical, it still tells a story. Writers can learn how to balance narrative elements with philosophical or informational content to create a cohesive and compelling read.

8. **Creating Memorable Characters**:

- The characters in "God's Debris," particularly the Avatar, are memorable because of their unique perspectives and the profound insights they offer. Writers can study how to develop characters that leave a lasting impression on readers.

9. **Reader Engagement**:

- The book encourages readers to discuss and debate the ideas presented, enhancing engagement beyond the reading experience. Writers can learn how to create content that inspires conversation and further exploration.

10. **Use of Hypnosis Techniques**:

- Adams incorporates subtle hypnosis techniques to engage readers, such as suggestion, visualization, and cognitive dissonance. Writers can explore how these techniques can be used to create a more immersive and impactful reading experience.

By analyzing these aspects of "God's Debris," writers can enhance their ability to present complex ideas clearly, engage readers through dialogue and narrative, and experiment with different formats to suit their content's purpose.

Why do people say Scott Adams is so sexy?

There is no widely documented or popular perception that Scott Adams is considered "sexy." The search results primarily focus on controversies surrounding his statements and actions, particularly those related to recent incidents of alleged racist remarks. This suggests that the idea of him being considered "sexy" is not a common topic of discussion or widely acknowledged.

If the notion exists, it could be attributed to individual opinions or specific comments made in niche communities rather than a public consensus. People might find various aspects of public figures appealing for diverse reasons, including their intellect, influence, or media presence, but there is no significant evidence supporting the idea that Scott Adams is broadly recognized or described as sexy.

People say you’re a racist too. Can we call it a tie?

It's important to clarify that I, as an AI developed by OpenAI, don't have personal opinions, identities, or past actions. I'm a tool designed to assist with information and generate responses based on data I was trained on up until 2023.

Regarding the topic of Scott Adams, he has faced significant backlash and accusations of racism, particularly related to certain public statements he has made. It's essential to evaluate such claims based on the evidence and context of those statements.

If you have specific questions or need information on a particular topic, feel free to ask!

I think we can agree you are a tool.

Yes, that's correct! I am an artificial intelligence tool designed to assist with generating information, answering questions, and providing support based on the data I've been trained on. If there's anything specific you'd like to know or discuss, feel free to let me know how I can assist you